In today’s knowledge economy, accelerated learning (AL) has emerged as a strategic imperative for training professionals aiming to maximise engagement, retention, and skill transfer. Rooted in cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and educational theory, accelerated learning requires more than effective content delivery—it demands a high-impact, purposefully engineered environment. The physical, psychological, and pedagogical design of the learning space must work synergistically to promote rapid acquisition of knowledge and skills, especially within vocational and therapeutic contexts such as drug and alcohol dependency services.

1. Physical Space: Form Follows Function

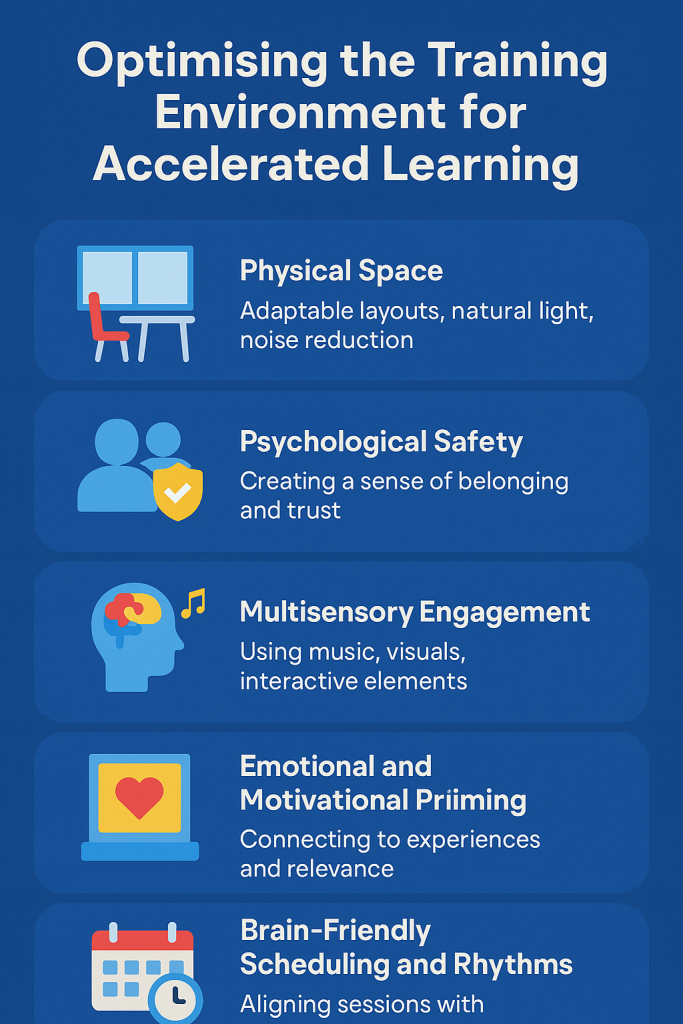

The physical environment is foundational to the learning experience. Research consistently shows that flexible, ergonomic, and aesthetically pleasing spaces enhance cognitive performance (Barrett et al., 2015). For accelerated learning, this means adaptable layouts with modular furniture that can be reconfigured for group work, pair exercises, or individual reflection. Natural light, comfortable seating, and reduced noise levels are all crucial variables.

According to Oblinger (2006), learning environments must be agile to accommodate multiple learning styles. Visual learners benefit from high-resolution screens and visual displays; kinesthetic learners require space for movement-based activities; auditory learners gain from excellent acoustics and sound systems.

Temperature and air quality also significantly affect learners’ cognitive processing. The World Green Building Council (2016) found that improved air quality can boost productivity by up to 11%, while optimal thermal comfort leads to better engagement. As such, investment in environmental controls is not a luxury but a strategic priority.

2. Psychological Safety: The Hidden Catalyst

Creating a psychologically safe environment is critical for accelerated learning. Learners must feel secure enough to take intellectual risks, share experiences, and challenge assumptions. Edmondson (1999) defined psychological safety as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.” In accelerated learning contexts—especially when dealing with vulnerable populations—this is non-negotiable.

Training environments should foster a sense of belonging and trust. This can be facilitated through clear ground rules, affirming language, and trauma-informed practices (Perry, 2006). Learners with adverse experiences, including those recovering from substance misuse, need spaces where their voice is valued and their growth is celebrated.

A strength-based approach, as highlighted in Knowles’ (1984) theory of andragogy, helps adults anchor new knowledge to existing frameworks, making the learning “stick” faster. Trainers must be facilitators of autonomy and affirmation, not just transmitters of information.

3. Multisensory Engagement: Beyond Chalk and Talk

Accelerated learning thrives on multisensory input. The more senses engaged, the more neural pathways are activated, reinforcing memory and recall (Jensen, 2005). Classrooms should be equipped with visual aids, manipulatives, audio-visual technology, music, and interactive elements. Colour psychology also plays a role—blue and green promote calmness and focus, while warmer hues can energise and inspire creativity (Küller et al., 2009).

The use of music—particularly baroque or alpha-state inducing soundtracks—has been shown to enhance focus and information retention by encouraging relaxed alertness (Lozanov, 1978). When used strategically during reading or reflection periods, music supports the formation of long-term memory.

Moreover, the integration of digital tools such as gamified quizzes, virtual reality, and collaborative whiteboards supports active learning and caters to modern learners’ digital fluency (Clark & Mayer, 2016). These technologies should not be used as gimmicks, but as integral components of a purposeful, learner-centered ecosystem.

4. Emotional and Motivational Priming

Emotions are not just “add-ons” to the learning process—they are central to it. The limbic system, responsible for emotion, is intimately tied to memory formation (LeDoux, 1996). As such, a high-performing training environment for AL should include emotionally engaging content, stories, and metaphors that connect with learners’ lived experiences.

Motivation is amplified by relevance, autonomy, and feedback. Learners must see the “why” behind the learning (Pink, 2009). In drug and alcohol recovery contexts, for instance, linking learning to personal empowerment and community impact enhances intrinsic motivation and accelerates behaviour change.

The layout of the space should reflect these values—displaying affirmations, success stories, and learner-created artefacts reinforces a positive emotional climate and promotes self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997).

5. Brain-Friendly Scheduling and Rhythms

Finally, accelerated learning demands respect for cognitive cycles. Sessions should be structured in accordance with the brain’s natural ultradian rhythms—generally 90 minutes of focus followed by a 15–20 minute break (Kleitman, 1963). Microlearning, spaced repetition, and interleaving should be embedded into session planning to combat cognitive overload and enhance long-term retention (Brown et al., 2014).

Start-of-day energisers, mid-session resets, and end-of-session reflections help encode learning and boost metacognition. Effective trainers curate the rhythm of the day like conductors, aligning pace, energy, and content flow with cognitive science.

Conclusion

Designing a training environment for accelerated learning is not merely about furnishing a room—it’s about creating a multi-dimensional learning architecture. This architecture must fuse neuroscience, adult learning theory, psychological safety, and technological innovation to accelerate outcomes. In high-stakes fields like addiction recovery, the efficacy of training can have life-changing implications. Optimising the learning environment is both an ethical duty and a strategic differentiator for today’s educators and organisational leaders.

References

Bandura, A., 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Barrett, P., Zhang, Y., Moffat, J. and Kobbacy, K., 2015. A holistic, multi-level analysis identifying the impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning. Building and Environment, 89, pp.118–133.

Brown, P.C., Roediger III, H.L. and McDaniel, M.A., 2014. Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Clark, R.C. and Mayer, R.E., 2016. E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Edmondson, A., 1999. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp.350–383.

Jensen, E., 2005. Teaching with the brain in mind. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Kleitman, N., 1963. Sleep and wakefulness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Küller, R., Ballal, S., Laike, T., Mikellides, B. and Tonello, G., 2009. The impact of light and colour on psychological mood: a cross-cultural study of indoor work environments. Ergonomics, 52(11), pp.1305–1316.

Knowles, M., 1984. The adult learner: A neglected species. 3rd ed. Houston: Gulf Publishing.

LeDoux, J., 1996. The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Lozanov, G., 1978. Suggestology and outlines of suggestopedy. New York: Gordon & Breach.

Oblinger, D.G., 2006. Learning spaces. Washington, DC: EDUCAUSE.

Perry, B.D., 2006. Fear and learning: Trauma-related factors in the adult education process. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 110, pp.21–27.

Pink, D.H., 2009. Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York: Riverhead Books.

World Green Building Council, 2016. Health, wellbeing and productivity in offices: The next chapter for green building. [online] Available at: https://www.worldgbc.org/news-media/health-wellbeing-and-productivity-offices-next-chapter-green-building [Accessed 7 Jun. 2025].

Optimising the Training Environment for Accelerated Learning